Model Evaluation

Statistical LearningGiving an estimate of generalization error in Machine Learning is vital.

This is to minimize risk given a hypothesis space \(\mathcal{H}\). To simplyfy matters assume the hypothesis space consists of a finilite set of estimators \[\mathcal{H}=\{h_1,h_2,\dots,h_M\}\]. Given a loss function \(L\) which we for simplicity assume is the 0-1 loss \[L(\hat{y},y)=1_{\{\hat{y}\neq y\}}(\hat{y},y)\]. Risk is then defined as

\[ \begin{aligned} R(h)&=\mathbb{E}[L(h(X),Y)] \\ &=\int L(h(x),y)d\mathbb{P}_{X,Y}(dx,dy) \end{aligned} \]

The main objective is to solve

\[ \underset{h\in\mathcal{H}}{\text{argmin}} \ R(h) \]

That is, the expected loss over over the hypothesis space. We don’t have this distribution \(\mathbb{P}_{X,Y}\) but we have samples from it. We therefore approximate this risk in practice using the samples. One way is to use the empirical risk:

\[ \begin{aligned} \hat{R}(h)=\sum_{i=1}^NL(h(x_i),y_i) \end{aligned} \]

and then try to minimize

\[ \underset{h\in\mathcal{H}}{\text{argmin}} \ \hat{R}(h) \]

This is known as Empirical Risk Mimimization (ERM).

Theory

Lets first go through a learning bound which can be used to justify the training validation split given the above objective.

Assume \(H<\infty\) and \[1_{\{\hat{y}\neq y\}}(\hat{y},y)\], then

\[ \forall\epsilon>0:\mathbb{P}\left(\max_{h\in\mathcal{H}}\vert R(h)-\hat{R}(h)\vert>\epsilon\right)\leq 2\vert \mathcal{H}\vert e^{-2N\epsilon^2} \]

or equivalently

\[ \forall\delta>0:\mathbb{P}\left(\max_{h\in\mathcal{H}}\vert R(h)-\hat{R}(h)\vert >\sqrt{\frac{\log(\vert \mathcal{H}\vert )+\log(\frac{2}{\delta})}{2N}}\right)\leq\delta \]

Proof. Let \(\epsilon>0\) use the Union Bound and Hoeffding’s Inequality

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb{P}\left(\max_{h\in\mathcal{H}}\vert R(h)-\hat{R}(h)\vert >\epsilon\right)&=\mathbb{P}\left(\bigcup_{h\in\mathcal{H}}\vert R(h)-\hat{R}(h)\vert >\epsilon\right)\\ &\leq\sum_{h\in\mathcal{H}} \mathbb{P}\left(\vert R(h)-\hat{R}(h)\vert >\epsilon\right) \\ &\leq 2\vert \mathcal{H}\vert e^{-2N\epsilon^2} \end{aligned} \]

Observing that

\[ \delta=2\vert \mathcal{H}\vert e^{-2N\epsilon^2}\Leftrightarrow \epsilon=\sqrt{\frac{\log(\vert \mathcal{H}\vert )+\log(\frac{2}{\delta})}{2N}} \]

one sees the equivalent statement. QED.

The above theorem states a learning bound. If \(\vert\mathcal{H}\vert<\infty\) then with probability less than or equal to \(1-\delta\)

\[ \forall h\in\mathcal{H}:R(h)\leq\hat{R}(h)+\sqrt{\frac{\log{\vert \mathcal{H}\vert +\log\frac{2}{\delta}}}{2N}} \]

Practice

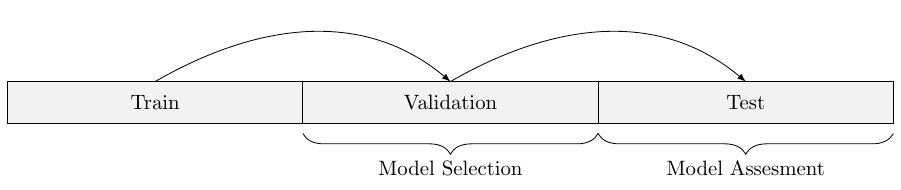

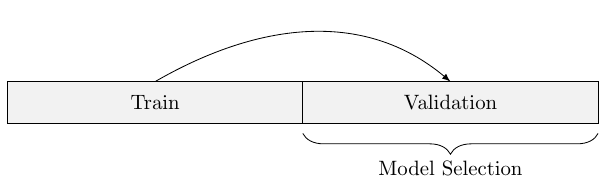

In practice one usually splits the entire dataset into three datasets: A Training dataset which is used for training the models, \(\sim50\%\) of the data, and a validation- and test-dataset, \(\sim25\%\) each, which is used for validating and testing the models.

The models are trained on the training dataset, using an algorithm, the performance of this trained model is then evaluated by predicting onto the validation dataset. One does this for multiple models and then selects the best performing one.

To theoretically justify this approach one can use the above generalization bound. Assume we have tried our luck and fitted \(1\) mio. different models \[\mathcal{H}=\{h_1,h_2,\dots,h_{1000000}\}\] on the training dataset. These models could consist of KNN for different \(k\), classification trees for different depths, random forests for different number of trees and depths for each tree and so on.

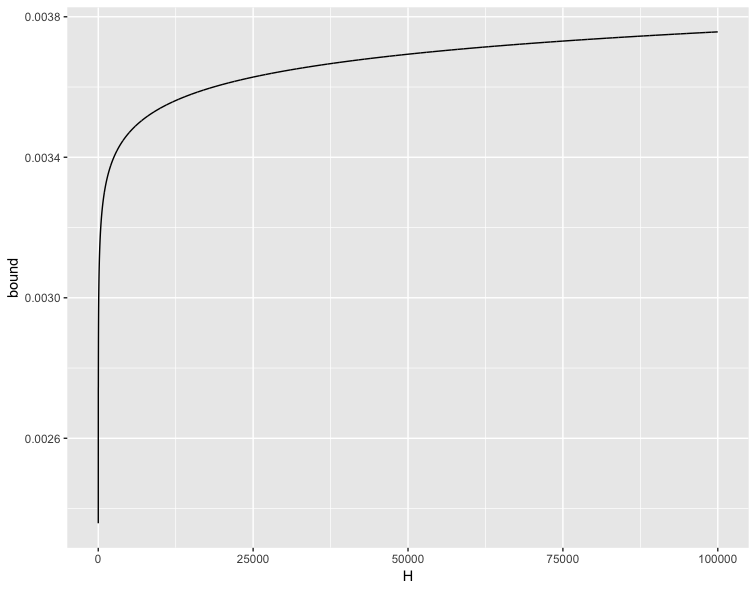

The above generalization bound gives a worst case performance with some probability. Assume we want to be sure that our model performs well with a probability of \(0.95\), in above \(\delta=0.05\), and that we have a validation sample of size \(1\) mio.

We find a classifier which has an error rate of only \(0.001\), how well will it then peform with 95% probability on new data? Answer:

\[ 0.001+\sqrt{\frac{\log 10^6 + \log\frac{2}{0.05}}{2 \cdot 10^6}} = 0.003539520 \]

Thats pretty close with a high probability. Varying the size on the hypothesis space has only a small effect on the bound which is quite remarkable.

The bound can be stated more loosly as: With probability \(1-\delta\)

\[ \begin{aligned} R(h)&\leq\hat{R}(h)+O(\sqrt{\frac{\log_2\vert \mathcal{H}\vert}{N}})\\ &=\hat{R}(h)+\Omega(\mathcal{H},N) \end{aligned} \]

The

\[ \log_2\vert\mathcal{H}\vert \]

has a nice representation as the number of bits needed to represent \(\mathcal{H}\), which seems like a natural measure to measure the complexity of a finite hypothesis space.

Similar bound holds on the testing dataset, which is used give to the user of the model as an assesment of performance, the complexity term \(\Omega(\mathcal{H},N)\) is then much smaller, because one usually only selects one model to test in practice: The best one on the validation set.

Above is some of my interpretations of chapter 1 in [1].

References

[1] Foundations of Machine Learning (Adaptive Computation and

Machine Learning series), 2012. Mehryar Mohri, Afshin

Rostamizadeh, Ameet Talwalkar

by Mehryar Mohri, Afshin Rostamizadeh, Ameet Talwalkar.

Comments

Feel free to comment here below. A Github account is required.